Over the summer, I received a spreadsheet full of comments left by attendees for a talk that I had delivered the previous week. Let me first start off by saying that it’s atypical for me to receive a spreadsheet full of feedback. For the vast majority of events, the organizers send me a summary or they complete our Change Coaches client survey. This was one of the few pro bono engagements I agreed to this year, so it’s a bit different than the usual corporate event. Now I’m questioning if I should continue accepting these opportunities.

To give you some specifics, the commenter criticized a “lack of depth” in my presentation and called me “judgmental and righteous” while insisting that all I cared about was “being a Black woman.” They finished by saying “I suggest she take some public speaking courses and [sic] how to present.” While this was an extreme outlier, I’m not the only one who felt their accusations were extreme and deliberately harmful. I knew someone who was in the room with me during the presentation, and they couldn’t believe someone came away with that perception of it. Others said it was straight-up racist.

Fortunately, when I received the feedback, I was physically surrounded by a supportive community at a conference. This softened the blow quite a bit. But I’d like to share a bit more about how I chose to handle it while providing some recommendations for event organizers and facilitators on how to manage nefarious feedback more effectively. If this article provokes any thoughts or insights for you, please leave me a comment. I’d love to have a productive discussion.

My Knee-jerk Reaction

I felt violently attacked and my first reaction was that I was very upset. When I recited the comment to others, they deeply empathized and validated me. Soon, I reminded myself that I know how to navigate stuff like this — I started by taking a few breaths to process how I felt and put the terrible critique into perspective. First of all, as mentioned earlier, the comment was an extreme outlier alongside many more actionable and congratulatory comments. I acknowledged that first and foremost. Second, I began dissecting the actual talk. What could make someone leave a comment like this? Do I have any part in this at all? This wasn’t a workshop or even my usual keynote, so of course, I didn’t go to the same depth as I do with paid engagements. But I have given this talk several times before with great feedback.

Running out of logical explanations, eventually I concluded that because they mentioned my race, gender, and personality, the content of the feedback was very likely more personal than substantial. I looked at it this way — if I had asked for face-to-face feedback from the audience after my talk, this person never would have said what they said. They were likely looking for something to complain about, and my race and gender made easy targets.

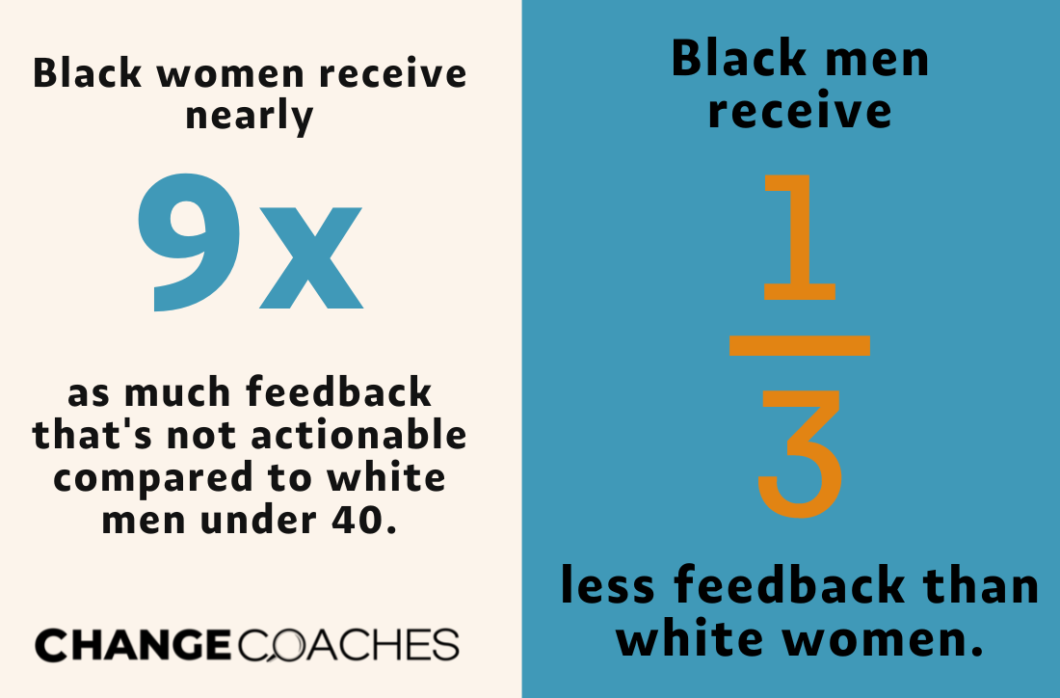

A recent study on performance reviews backs this up. There are major disparities in the quantity and quality of feedback minority groups receive in the workplace. Survey data from 25,000 people at 250 organizations shows that certain groups are more likely to receive feedback about their personality than their behavior or work outcomes, including Black people, Latinx people, workers over 40, and women. As the Textio report points out, people who receive less constructive feedback don’t get the same opportunities to progress in their careers and end up earning lower salaries.

One of the biggest takeaways from this study is that high-performing women are significantly more likely to receive critical feedback that’s overtly negative rather than constructive. Here are a few more highlights:

- Women receive 22% more feedback about their personalities than men do. Women also receive 30% more exaggerated feedback than men.

- Black men receive 1/3 less feedback than white women on average, as measured by word count.

- Black women receive nearly 9x as much feedback that’s not actionable compared to white men under 40.

The tone and content of the feedback I received are consistent with this study! It happens more than you’d think, so if you haven’t done anything to prevent this sort of bias in your organization and you don’t think it’s an issue, you might not be looking closely enough.

How to Handle Malicious Feedback

As a professional who was brought into this event specifically to talk about belonging, I felt compelled to contact the event staff to make them aware of my experience and provide them with some feedback. While I provided these suggestions to this specific events team, they can apply to almost any situation where you might be collecting and sharing feedback on someone else’s behalf:

- Consider screening the responses you receive and putting comments into perspective before sharing them with the speaker. At the very least, remove anything that mentions race, gender, or any other characteristics your presenter cannot change.

- If you are an event organizer, the feedback should first and foremost be for you. Before sharing with presenters, ask yourself, what is the value of sharing this? Some say that feedback in itself is a gift, but I would argue that blanket statements like this aren’t always true. How qualified is the group to give the feedback? Usually, not very, so it’s important to put structures in place to keep feedback focused. Try to limit the solicited feedback to questions that measure true learning effectiveness. If you notice outliers that are wildly different from the other responses, ask yourself if you should include them at all.

- This last point might be hard for some to hear, but off-color comments might say more about the audience and who they are willing to hear from than the speaker they are criticizing.

If you find yourself in my position, receiving feedback after a presentation that may be unfiltered, unhelpful, and malicious in nature, I have some tips for you too:

- Consider if you need to read the feedback in the first place, and if you do, put it into perspective. I know some speakers that don’t even read spreadsheet comments because many tell me there are always outliers!

- Avoid negativity bias by spending just as much time on the good comments.

- Find your people. I was with my community when I got the news, so that made it easier.

- Use the feedback to inform your future strategy, not to make judgments about yourself. You are not going to be for everyone.

- If there is a grain of truth, implement it. I thought we had agreed on a keynote since it was unpaid, but it was apparently a workshop.

- Honor your feelings and move on. You don’t deserve to let the trolls ruin your day!

Trust Your Gut and Choose to Do Better

Although I knew what my gut was telling me, everything was put in perspective when I shared this malicious feedback with a white male colleague who appeared to be fighting off tears in his eyes after just hearing about it. You know the intent was harmful when others who are not part of the targeted group have a visceral reaction. Even if you aren’t 100% sure what might constitute “hate speech,” “abuse,” or “trauma,” your gut will tell you when there’s a potential problem. Listen to it and explore your choices carefully.

I’ve created a few different tools to help you examine your own leadership practice and shine a light on some areas where you can help others feel a sense of belonging. Order my book Leading Below the Surface and sign up for our allyship email challenge today.